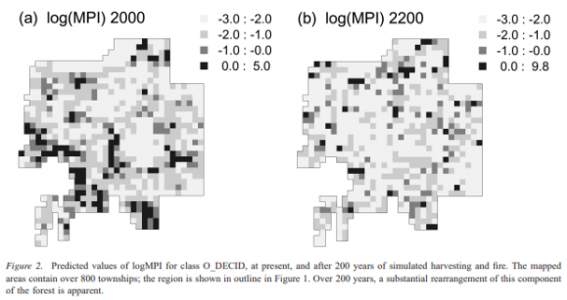

Industries and other human activities have become the main cause of the rapidly changing forest structure in Canadian boreal forests. As the Canadian governments are now aware of the detrimental effects of such large-scale industrial activities, they are committed to sustainable forest management. In Cumming and Vernier’s research, they address the spatial resolution and scaling problem in forest management. The study region focuses on 75,000 km2 of the boreal mixedwood forest on the southern edge of a large forest estate in northeast Alberta. However, they acknowledge that the study of forest tenure arrangements and the size of large wildfires would mean that strategic assessments need to be conducted over large extents (e.g. 100,000 km2) and periods of time (e.g. 200 years) (Cumming and Vernier, 2002). Thus, Cumming and Vernier present a statistical solution to modelling large regions from low-resolution data, using a stand attribute table (SAT) and the FRAGSTATS program.

Cumming and Vernier determined a correlation between landscape metrics measured with stand attribute metrics (STMs) and landscape pattern metrics (LPM). In the research, it was determined that spatially aggregated data can model landscape configuration or spatial arrangement of patches within landscapes. Although only three landscape variables were considered from the SAT, the statistical model was able to identify more than 73% of the joint variation in five landscape pattern metrics (Cumming and Vernier, 2002). However, some results may vary due to the use of different programs to compute spatial metrics. Anyhow, Cumming and Vernier list the advantages of low spatial resolution modelling: simplified model development and data acquisition; simulation studies can be conducted at regional extents; and shorter execution time in modelling (Cumming and Vernier, 2002). Although STMs and LPMs can be useful in the statistical analysis, results could change when it is applied to real scenarios.

Learning Significance